金在德的《棕色》、反本質主義與當代跨文化舞蹈

劇評 | by 尹水蓮 | 2022-12-19

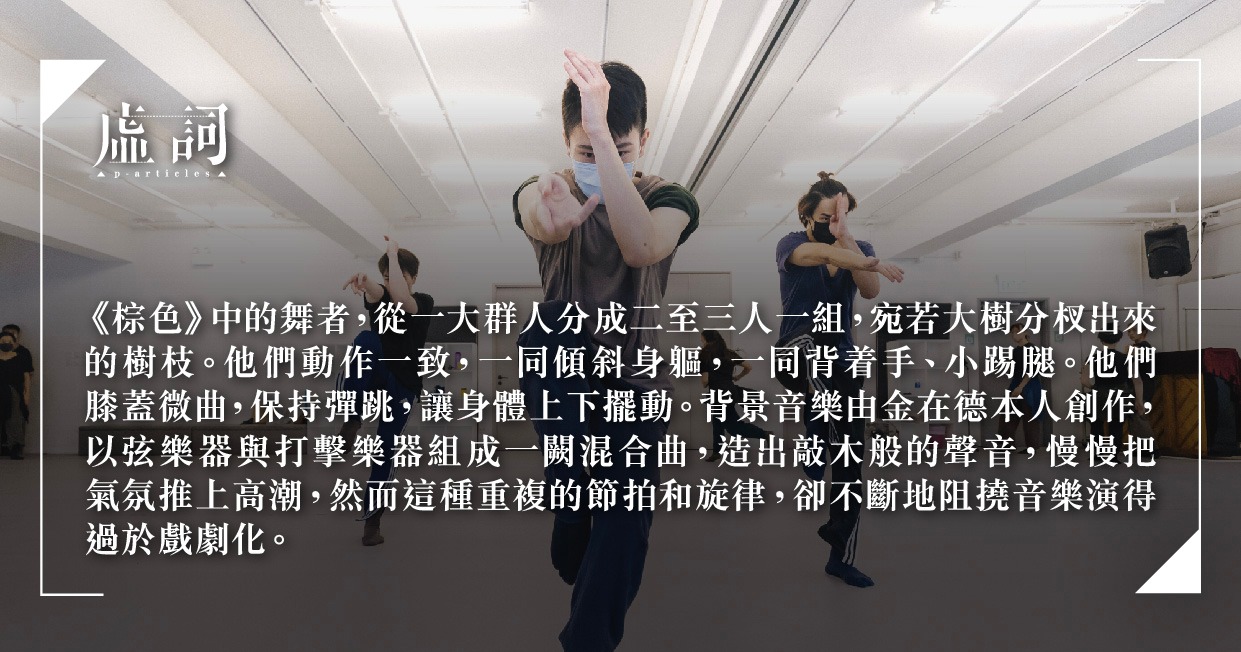

《棕色》中的舞者,從一大群人分成二至三人一組,宛若大樹分杈出來的樹枝。他們動作一致,一同傾斜身軀,一同背着手、小踢腿。他們膝蓋微曲,保持彈跳,讓身體上下擺動。背景音樂由金在德本人創作,以弦樂器與打擊樂器組成一闕混合曲,造出敲木般的聲音,慢慢把氣氛推上高潮,然而這種重複的節拍和旋律,卻不斷地阻撓音樂演得過於戲劇化。

韓國人如我,能輕易看出這作品有部份元素來自傳統音樂和舞蹈,或至少受其影響。當中的小踢腿、平衡動作中的抬腳、把袖甩到肩後的姿勢和彈跳動作等,都令我想起韓國的巫俗舞salpuri的步法以及小鼓舞chaesangsogochum中的反覆彈跳,而聲音則近似牙箏ajaeng(七弦低音樂器)和韓國傳統鼓buk。

當然,即使觀眾不知道這些動作背後的文化底蘊,也不會影響他們的觀賞體驗。事實上,這正正就是編舞家的意圖,把《棕色》裡的文化符號盡量保持模糊抽象,即使這些文化符號仍會體現在CCDC的舞者身上。如有觀眾在金在德的編舞中試圖辨識當中的特定文化標籤,那只會註定徒勞無功,因為金在德讓舞者戴上大地色調的面具和手套,把舞者的肉體、皮膚和面部表情盡皆隱去。金在德刻意不把《棕色》納入任何特定的文化或民族類別之中,亦拒絕把這次新作簡化成「當傳統遇上當代藝術」的陳詞濫調或只是作為韓國舞蹈的港版演出。

在這個脈絡下,《棕色》能否讓我們既能避免陷入文化本質主義,亦能思索這場舞蹈的文化身份?當這個作品是由香港舞者表演時,當中民族與傳統元素所蘊藏的「韓國性」會否轉化為其他東西?又或者從另一角度看,當CCDC舞者演出金在德的作品時,會否令他們重新理解自身的文化身份甚至偏見?《棕色》作為一個跨文化作品,如何同時批判我們觀眾和藝術家總把看到的事物納入文化符號中的慣性?

這篇文章的目的,並非為了界定金在德與CCDC合作的《棕色》是否屬於跨文化作品;相反,我更有興趣探討金在德的這個新作如何違反常規,令現存的當代舞蹈慣語和傳統文化元素變得更為複雜,尤其當傳統文化元素乃金在德作品在國際藝壇的標誌風格。也就是說,此作打開了一個新的空間,以供大家思考何謂當代舞蹈中的「當代」、我們如何使用色彩和觸感作為編舞的框架、以及文化差異如何可共存於一個作品之中,而不需訴諸文化本質主義及刻板印象(註)1)。

了解跨文化表演(及其不滿)

雖然這篇文章無法複述跨文化表演的歷史和理論,但即使只是扼要回顧其概念和整體背景亦有其用處,尤其對於初次接觸跨文化主義的觀眾而言。

跨文化主義(Interculturalism)指的是一系列觀點、方法、技術、實踐和闡釋,將跨文化對話和文化揉雜作為表演製作的關鍵主題和方法。舞蹈和戲劇中的跨文化主義在1980及1990年代迎來復興,以回應當時的批判、前衛、後殖民和多元文化思潮,試圖對抗舞蹈和戲劇界中的歐洲霸權主義。從跨文化的觀點來說,兩種或以上文化的匯集,並非僅僅為了展示文化的聚合,而是為了創造一種嶄新的另類方法,以超越現有形式的舞蹈和戲劇製作。最易令人想起的,就是把歐洲經典作品如莎士比亞的《暴風雨》改編成後殖民的回應,並融入亞洲傳統如日本能劇(以蜷川幸雄1988年的作品為例),而非純粹重構伊麗莎白時代的表演。在這層意義上,中文的「跨」字尤其貼切,因為有跨越或超越(文化)邊界的意味。

然而,表演藝術中的跨文化主義卻一直備受批評,主要來自非西方評論家、藝術家和學者,他們觀察到跨文化表演藝術通常由歐美藝術家(或受過歐洲傳統訓練的非西方藝術家)創作,並經常挪用或嚴重依賴亞洲或非西方文化作為素材。在許多跨文化表演中,非西方的本地和土著元素會被描繪成民間、傳統或文化元素,同時會被歐洲與北美「當代」戲劇與舞蹈的美學語言改作他用,把「非西方」定位為「前現代的他者」。. 即使亞洲創作人亦不能倖免於歐洲霸權的影響,因為亞洲藝術家也會挪用傳統元素來強化他們自己的東方主義幻想(2)。從這個意義上說,大家可能會問(回想一下跨文化主義中的「跨」字):當文化關係總是充滿權力不均、不平等與階級制度時,有誰承受得起跨越文化邊界的代價?事實上,多位藝術家和評論家亦曾提出類似問題。Rustom Bharucha對 Peter Brook作品《Mahabharata》的批評(註3)或是Ananya Chatterjea對跨文化當代舞蹈的觀察,均關注到許多跨文化作品經常強化歐美藝術家與世界其他地區之間的不平等關係,例如Chatterjea就曾指出:

把動作內容從結構和語境中割裂出來的狀況,以往一直困擾著多元文化作品創作,現在亦於全球及跨文化項目中依然存在。來自亞洲和非洲的形式和表演者經常被用於這些演出中,但目的只為確保歐美美學的優勢。(註4)

有見及此,與其思考何謂(成功的)跨文化表演,其實像關珊珊和張懿文等學者反而引導大家關注藝術家如何努力達至跨文化表演的道德層面,或是如何在歐美文化霸權力場以外建立新的地緣政治知識據點(註5)。如果從這個習面思考金在德《棕色》的觀賞體驗,我們會如何看待這個作品試圖取代歐洲中心主義的當代美學以創造一種全新動作語言的藝術策略?

金在德的同時代性及反本質主義

對於金在德以及他最近的作品,真正成為「當代的」(contemporary)及「同時代性」(contemporaneity)的並不僅是對過去/傳統的倒置,例如使用明顯的實驗主義元素如電子舞曲、金屬前衛服裝及複雜的燈光設置等,這些元素只不過是藝術家在尋索自己藝術語言的漫長過程中的現代主義過渡時期。金在德在他最近的作品中(包括《棕色》)試圖重返基本步,研究日常物品當中最根本的元素、我們從小習得的動作(比如之前提到的傳統動作),以及我們周遭環境的顏色:泥、樹、雲、空氣。此作的音樂一直在原聲與電子之間搖擺不定,時而壓抑,時而爆發;然而貫穿箇中所有變化的,是藝術家刻意透過大提琴和類似牙箏的弦樂所帶出的木頭觸感,或是透過棕色面具和手套所帶出的視覺衝擊,令跳舞的軀體轉變為無名的「後人類」形象。同樣地,這些元素會令觀眾聯想起某些形象,然而不同觀眾卻會根據自身背景而聯想起不同事物。棕色在韓國或會令人聯想起天然粘土,在澳洲卻會令人想起當地的革木樹。

這些原始而基本的元素,迫使觀眾關注舞台上產生的新舞蹈語言,而非尋找典型的文化標識,亦促使CCDC舞者和香港觀眾直接面對自己的文化偏見:《棕色》的「同時代性」因此成為一種「並非文化本質主義的文化意涵」。正因如此,金在德刻意避開畢直挺立的軀幹動作,亦避免把棕色與特定文化起源有所聯繫,亦拒絕將聲音標上「亞洲」或「西方」特質。在排練過程中,部份年紀較輕的CCDC舞者往往要多番嘗試,方能理解金在德的哲學精髓,包括解開和反思他們於歐美當代舞或西方古典芭蕾舞所習得的身體認知。然而,這並不等於要求舞者學習韓國文化或回歸中華文化根源。把過往的訓練「鬆綁」,是要令舞者審視自身的文化身份,同時轉向一種嶄新的反本質主義編舞方式,而這種編舞仍會尊重編舞者與舞者之間、作品與當地觀眾之間、以及編舞者自己的過去、現在與未來美學之間的張力和跨文化對話。

逆紋而舞

某程度上,金在德的新作要求我們所有人都「逆紋而舞」(“dance” against the grain)(譯註:英文習語「against the grain」有「違反常理」之意)。「grain」一字亦解作木紋,即「(木材)纖維或粒子的縱向排列」(註6)金在德與CCDC舞者的合作,擾亂了一般人視為正常熟悉之物的認知(即舞台上線性「排列」的文化),藉此希望令我們盡可能以一種革新、發自肺腑、最重要的是當代的方式,批判地重新思考跨文化作品。

(1) 這篇文章所提出的許多觀點和提問,來自我與金在德的採訪(2022年10月4日,南韓果川市)。

(2) 請參閱張懿文(2021)評論跨文化及跨國亞洲表演作品《千個舞台,但我從未完全活過》(2021)中關於再現政治的文章:

張懿文,《【Reread:再批評】從兩廳院Taiwan Week性別失衡危機談起——論國家級表演場館之自我定位、國際想像與本地藝術生態(上)》。表演藝術評論台。2021年7月12日。

(3) Rustom Bharucha. 1988. “Peter Brook’s ‘Mahabharata’: A View from India.” Economic and Political Weekly 23 (32): 1642-1647.

(4) Ananya Chatterjea. 2013. “On the Value of Mistranslations and Contaminations: The Category of ‘Contemporary Choreography’ in Asian Dance.” Dance Research Journal 45 (1): 7-21, 14.

(5) SanSan Kwan. 2014. “Even as We Keep Trying: An Ethics of Interculturalism in Jérôme Bel’s Pichet Klunchun and Myself.” Theatre Survey 55 (2): 185-201; I-Wen Chang. 2022. “Dancing me from South to South: on Wu-Kang Chen and Pichet Klunchun’s intercultural performance.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 23 (4): 611-626.

(6) “Grain.” Entry 15. The Oxford English Dictionary.

英語原文

Kim Jaeduk’s Brown, Anti-Essentialism, and Contemporary Intercultural Dance

Written by: YOON Soo Ryon (Performance Researcher)

In Brown, dancers diverge into groups of two or three from one large mass as if to branch out from a tree. They proceed to movements in unison that feature leaning torsos and small kicks with their hands on their backs. Their knees are ever so slightly bent enough to allow for continuously elastic and bouncy moves, letting their bodies bob up and down. Background music of Kim Jaeduk’s own composition plays a medley of string instruments and percussions resembling the sounds of knocking on wood, which slowly builds up to its climactic moment. Yet the repetition of beats and melodies somehow constantly resists overly dramatic development of music.

To Koreans like myself, some of these may be easily recognizable as rooted in, or at least inspired by, traditional music and dance. Small kicks, lifted feet in a balancing act, gestures of tossing sleeves behind shoulders, and springy movements remind me of the footsteps or baldidim in salpuri (shamanic dance) and repeated bounce or gulsin in chaesangsogochum (hand-held small drum dance). The sounds resemble that of ajaeng (7-string bass instrument) and buk (drum).

Of course, even if an audience member had no idea what the cultural heritage behind these movements was, it does not impact one’s viewing experiences. In fact, it is the choreographer’s very intention that the cultural signifiers in Brown remain as obscure and abstract as possible, even as they are still embodied by the CCDC dancers. Any audience efforts to identify Kim’s choreography with a specific cultural label will further fail because of the choreographer’s use of earth tone masks and gloves, which hide dancers’ flesh, skin, and facial expressions. Kim Jaeduk purposefully departs from territorializing Brown into any specific cultural or national category and resists the idea of reducing his new work to a contemporary-meets-tradition cliché or a Hong Kong version of Korean dance.

In this vein, can Brown demonstrate ways in which we can still consider a cultural identity of dance while avoiding cultural essentialism? Does the innate sense of Koreanness embodied through the traces of folk and traditional elements transform into something else, as the work is performed by Hong Kong-based dancers? Or, in another sense, does the experience of performing Kim’s piece change the CCDC dancers’ own sense of their cultural identities as well as biases? How does Brown attempt to work across different cultures while simultaneously critiquing our impulse as viewers and artists to contain something into a cultural symbol?

This essay is less interested in defining whether the Kim Jaeduk-CCDC collaboration Brown is intercultural or not. I am much more interested in reading the choreographer’s new work against the grain in terms of how it complicates existing contemporary dance idioms and traditional cultural elements, the latter being the iconic part of Kim’s oeuvre in the international context. This is to say that Kim’s Brown pries open a new space for thinking about what is contemporary in contemporary dance, how we use color and tactility as a framework for choreography, and how cultural differences co-exist within the work without resorting to cultural essentialism and stereotypes (1).

Understanding Intercultural Performance (and Its Discontent)

While this essay cannot rehearse the history and theories of intercultural performance, surveying its concept and overall context even briefly may be useful, particularly for the viewers who are introduced to interculturalism for the first time.

Interculturalism, commonly translated into 跨文化主義 in Canto-Chinese, refers to a range of perspectives, approaches, techniques, practices, and interpretations that privilege cross-cultural dialogue and hybridity as key themes and methods when it comes to performance making. Interculturalism in dance and theatre experienced resurgence between the 1980s and the 1990s in response to the emergence of critical, avant-garde, postcolonial, and multicultural thinking, especially as an attempt to decenter European hegemony in the field. From the intercultural perspectives, two or more cultures do not merely come together to showcase an assemblage of cultures; rather, they are meant to create a new and alternative method to dance and theatre making beyond existing forms. What comes to mind are the instances where European canons like Shakespeare’s The Tempest are rewritten as a postcolonial “talkback” to incorporate Asian traditions such as Japanese noh (e.g. Yukio Ninagawa’s 1988 production) rather than reconstructing the Elizabethan performance. The Chinese word “跨” seems apt in this sense, as it implies acts of crossing or exceeding (cultural) borders.

Interculturalism in performing arts, however, has been also met with criticism over the years, especially from non-Western critics, artists, and scholars who observe that intercultural performing arts often appropriate and heavily rely on using Asian or non-Western cultures as raw materials reworked by Euro-American artists (or by non-Western artists trained in the European tradition). In many intercultural performances, non-Western local and indigenous components are featured as folk, traditional, or cultural, while getting repurposed through the languages of Euro-North American “contemporary” theatre and dance aesthetics, which positions the non-West as the premodern Other. Asian practitioners themselves are not immune to the impact of European hegemony, as Asian artists also mobilize traditions to reinforce their own orientalist fantasies (2). In this sense, one may ask (and to recall the Chinese word “跨”): who can afford to cross the cultural borders when the cultural relationships are always already fraught with uneven power, inequality, and hierarchy? Indeed, many artists and critics have raised similar questions. Rustom Bharucha’s critique of Peter Brook’s Mahabharata (3) or Ananya Chatterjea’s observation of intercultural contemporary dance share concerns about how intercultural projects often continue to reinforce the unfair relationships between Euro-American artists and the rest of the world. Chatterjea, for instance, notes,

[T]he severing of movement content from structure and context that plagued past multicultural endeavors continues through the staging of global and intercultural projects where all too often forms and performers from Asia and Africa are mobilized only to ensure the ascendency of Euro-American aesthetics (4).

Given this, instead of thinking about what a (successful) intercultural performance looks like, scholars like SanSan Kwan and I-Wen Chang call our attention to artists’ constant efforts to approximate an ethical dimension of cross-cultural performance or formulate a new geopolitical site of knowledge outside the Euro-American force field of cultural hegemony (5). Situating our viewing experiences in this context, what do we now see as strategies in Kim Jaeduk’s Brown that displace Eurocentric contemporary aesthetics toward creating a new movement language?

Kim Jaeduk’s Contemporaneity and Anti-Essentialism

For Kim and in his recent works, what truly becomes contemporary (현대적 現代的) as well as contemporaneity (동시대성 同時代性) is not a mere inversion of the past/traditions: using obvious components of experimentalism such as electronic dance music, metallic avant-garde costumes, and complex lighting works are only part of the modernistic transitions in the long process of still finding one’s own artistic language in the present moment. In his recent works including Brown, Kim seeks to return to studying the most basic, fundamental elements of our everyday objects, gestures that we embody from a very early age (such as the traces of traditional movements I mentioned earlier), and colors of our surroundings, of soil, trees, cloud, air. The music throughout the piece oscillates between the acoustic and the electronic, sometimes subdued and at other times explosive. But permeating through all of these changes is Kim’s emphasis on the sensorial experiences of feeling the touch of wood through the cello and ajaeng-like string sounds or the visual impact of brown masks and gloves, which are meant to transform the dancing bodies into unnameable posthuman figures. Again, these components may conjure up certain images for viewers, but depending on their own contexts, they will mean different things. The color brown may appear to resemble that of natural clay used in Korea, but for some, it could be the color of the leatherwood native to Australia.

All of these raw, elementary components compel the audience members to pay attention to the new dance language being produced on stage, instead of looking for typical cultural identifiers, prompting both the CCDC dancers and local viewers to confront their own cultural biases: Brown’s contemporaneity thus becomes cultural without being culturally essentialist. Because of this, Kim purposefully avoids executing perfectly upright torso movements, or associating the color brown with culturally specific origins, or labeling the sounds with either “Asian” or “Western” qualities. During the rehearsal process, some of the young CCDC dancers often went through multiple trials to understand the essence of Kim’s philosophy, which required them to eventually undo and rethink their bodies trained in Euro-American contemporary dance or Western classical ballet. This did not, however, mean that the dancers had to learn Korean cultures or to return to their Chinese cultural roots. The undoing of their training prompted them to interrogate their own cultural identities while moving in a new, anti-essentialist choreography that still respected the tensions and intercultural dialogue present in the relationship between the choreographer and the dancers, between the work and the local viewers, between the choreographer’s own past, present, and future aesthetics.

Dancing against the Grain

In a way, Kim Jaeduk’s new work requires all of us to “dance” against the grain. The word “grain” is also used in “wood grain,” which refers to the “longitudinal arrangement of [wood] fibre or particles. (6)” By troubling what feels normal and familiar to us as the linear “arrangement” of cultures on stage, Kim Jaeduk, in collaboration with CCDC dancers, wants us to critically rethink the intercultural in progressive, visceral, and most importantly, contemporary ways as much as possible.

1. I draw many of the points and questions I raise here from my interview with Kim Jaeduk, 4 October 2022, Gwacheon, South Korea.

2. See I-Wen Chang’s piece (2021) on the politics of representation in intercultural and transnational Asian performance production A Thousand Stages, Yet I Have Never Quite Lived (2021): 張懿文, “【Reread:再批評】從兩廳院Taiwan Week性別失衡危機談起——論國家級表演場館之自我定位、國際想像與本地藝術生態(上)”. 表演藝術評論台. 12 July.

3. Rustom Bharucha. 1988. “Peter Brook’s ‘Mahabharata’: A View from India.” Economic and Political Weekly 23 (32): 1642-1647.

4. Ananya Chatterjea. 2013. “On the Value of Mistranslations and Contaminations: The Category of ‘Contemporary Choreography’ in Asian Dance.” Dance Research Journal 45 (1): 7-21, 14.

5. SanSan Kwan. 2014. “Even as We Keep Trying: An Ethics of Interculturalism in Jérôme Bel’s Pichet Klunchun and Myself.” Theatre Survey 55 (2): 185-201; I-Wen Chang. 2022. “Dancing me from South to South: on Wu-Kang Chen and Pichet Klunchun’s intercultural performance.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 23 (4): 611-626.

6.“Grain.” Entry 15. The Oxford English Dictionary.